We thought it would be good to review options for configuring an effective and inspiring mixing environment. We’ll pull together certain techniques that the Pro’s use, consider new ways to utilize some tools, and explore additional Pro Tools features that can significantly enhance the mixing process.

System Options

Anyone that has mixed before has seen how beefing up a system can facilitate taking on larger, more complex projects. Nowhere is this more imperative than when mixing. You just can’t get enough of certain items:

-

Control surface features. Mixing is all about making repeated control adjustments until you’ve gotten parameters just right. How do you make these adjustments? Perhaps largely using the graphical editing tools we explored last week, but everything else you do involves setting linear fader levels, rotary pot positions, and other types of controls. Control surfaces make these actions considerably easier, so it won’t be a surprise if you use these features more when mixing that at any other stage of the production process.

-

Screen real estate. With or without a control surface, mixing benefits from as much display capacity as possible. Besides having access to both the Mix and Edit windows, you’ll often want to show multiple plug-ins as well as other windows. Larger monitors are always good, but a second display is even better.

-

Processing power and RAM. The amount of number crunching going on within a mix can be staggering. Unless you’re making minimal use of signal processing, faster multi-processor or multi-core hosts for native systems—or additional DSP cards with an HD rig—will enable you to manage far more involved mixes. Likewise, additional RAM will boost general performance and enable the use of more plug-ins, particularly processor hogs like convolution reverbs.

-

Plug-ins. Of course, all of this processing power won’t help if you don’t have much in the way of plug-ins. The standard suite of Pro Tools plug-ins is a nice start, but you’ve already seen how additional Avid as well as third-party products can dramatically enhance your capabilities. For mixing, you may want to start by looking at additional ambience and effects processors, since these are not the strongest elements of the basic Pro Tools collection.

Screen Layout and Display Options

Although generally speaking most mixing beginners use systems with a single monitor with and without a basic control surface, you can imagine that display options can be much more dramatic with expanded systems. However, if you are fortunate enough to have two monitors and do not have a control surface, you’ll likely want to dedicate one monitor for the Mix window and the other for the Edit window. If you prefer to do most of your work using the Edit window, you might toggle between Edit and Mix on your main monitor and reserve the second for plug-ins as well as other frequently used windows (Memory Locations, Automation, etc.). With two monitors and a control surface, there’s rarely any reason to access the Mix window. Maximize the Edit window on the main monitor, and use the second as described above.

When using a single monitor, how can you optimize the display? Consider these options for the Edit window:

-

View the left (tracks/groups) column. Though you can use Groups List Keyboard Focus mode (introduced in the next topic) to enable and disable groups, you’ll miss some nice features without access to the Groups List.

-

Hide the Clips List. Yes, there are commands in the Clips List popup menu you might need when mixing, but some have shortcut equivalents, and much of the time these are not necessary.

-

Select inserts, sends, and I/O view options. The I/O column allows you to bring up Output windows and use quick shortcuts to access automation playlists, so this is a good option when you’re mixing primarily with the Edit window.

-

Show the Automation and Memory Location windows. These may be accessed frequently, so consider dedicating a typical area for them.

-

Hide the Transport window. At this stage, it just gets in the way, and you can display transport controls in the main Edit window toolbar and/or set the numeric keypad to Transport Mode for control of everything you need.

-

View one plug-in at a time. Though it can be really convenient to have more than one plug-in window on screen, they will quickly obscure the rest of the session. Alternatively, use the commands introduced below to facilitate working with multiple floating windows.

Your base display might look like this:

However, it is sometimes very useful to include multiple floating windows in your screen layout. For example, you might want to display several plug-in windows in order to compare EQ settings on various channels, or utilize a series of output windows to provide mixer-like functionality while maintaining the basic Edit window perspective. Some users don’t bother with such configurations, since it takes a bit of effort to open and close all of the windows. However, there are a couple of newer Pro Tools features that greatly facilitate these scenarios:

-

Hide floating windows. The command Window > Hide All Floating Windows makes it much easier to utilize multiple windows. Rather than closing and reopening floating windows manually—a minor but annoying hassle—you can simply hide them temporarily. You can also use the shortcut Command-Option-Control+W (Mac OS) or Control-Alt-Start+W (Windows).

-

Create custom Window Configurations. A handy part of the Pro Tools feature set is the ability to name, store, and recall the configuration of windows in a session as well as the view options of the primary windows.

Color Coding Preferences

Color coding is the type of feature that might seem trivial at first glance. However, it can really enhance the usability of sessions by providing an additional dimension of feedback that helps you differentiate repeated elements with similar features.

Three aspects of the Edit and Mix window displays can be customized with color coding preferences:

-

Color bars that appear in several locations

-

above and below each channel strip in the Mix window.

-

to the left of each track in the Edit window track area.

-

to the left of each track name in the Tracks List.

-

to the left of each group name in the Groups List.

-

-

Track area display in the Edit window

-

clip shading in Blocks or Waveform views.

-

waveform color when viewing automation playlists.

-

-

Shading between markers in the Markers ruler.

Note that of these options only the Track Color view affects the Mix window display.

Color coding selections are made in the Display preferences tab. Track Color Coding settings apply to all color bars, and Clip Color Coding settings determine clip and waveform shading. Marker ruler colors are enabled via the first checkbox, or when choosing the Marker Locations option for clips.

Display Contrast and Channel Strip Shading

How important is the brightness and contrast of the Pro Tools interface? Perhaps more than you’d think. Consider the dramatic changes made to the graphical user interface way back when version 8 was released:

A session opened in Pro Tools 7.4

The same session as of Pro Tools 8.

The difference is not subtle. If you’re like most people, you either love the updated interface… or can’t stand it! At that time, many who preferred the “classic” version liked the bright display and contrast that could make it easier to differentiate on-screen elements. Some who preferred the revised version found it more comfortable for viewing, especially during long sessions.

What do you think? Regardless, there are additional display options that allow you to modify the standard grey background if you find it unappealing. The Color Palette window can be used to customize interface colors, and in particular alter the shading of channel strips.

The Brightness slider can make a big difference for background contrast. You also might want to experiment with the Apply to Channel Strip button shown above, along with the Saturation slider, to shade channel backgrounds according to the active color coding preference.

Modifying and Deleting Groups

It’s not uncommon for you to want to modify characteristics of a group. For example, you might record new tracks that are consistent with an existing group, or find that you’d rather not have an Edit group also link track controls. In the past, you’d have to create a new group and overwrite the previous one to effectively modify it. That’s not necessary anymore:

-

Access the Modify Groups dialog using any of the following methods:

-

Select Modify Groups in the Edit Groups List or Mix Groups List popup menu.

-

In the Mix window, click on a track’s Group ID Indicator and select Modify in the popup menu.

-

Right-click or click and hold on the group name in the Edit Groups List or Mix Groups List, then select Modify in the popup menu.

-

-

Set the group parameters as you would when creating a new group, starting with the group ID.

1. The Remove button in the Modify Groups dialog provides an easy means for removing one or more tracks from the current group members.

2. The handy—but dangerous—All group (discussed shortly) can be modified to make it somewhat less dangerous by restricting it to only act as an Edit or Mix group.

Two of the methods for modifying groups also provide a means for deleting a designated group:

-

In the Mix window, click on a track’s Group ID Indicator and select Delete in the popup menu.

-

Right-click or click and hold on the group name in the Edit Groups List or Mix Groups List, then select Delete in the popup menu.

NOTE: Deleting groups is not undoable, so be certain you really want to do this. Don’t worry; you’ll be reminded. Also keep in mind that deleting groups leaves the actual tracks intact.

Stereo Tracks Versus Grouped Mono

Don’t discount the possibility that a grouped pair of mono tracks might occasionally be more effective than the typical stereo configuration. It’s true that a single stereo track is usually best for two-channel sources such as virtual instruments or stereo miking. However, you’ll sometimes want to treat one side of the pair differently than the other, like using a different plug-in on the left and right channels. In this case, it might be convenient to simply work with mono tracks but group them to easily adjust their general control settings.

Exploring Inserts and Real-Time Plug-Ins

In this section, we’ll explore a variety of aspects related to using channel inserts in Pro Tools sessions. We’ll start by considering several general insert issues, including the potential for misusing plug-ins, insert signal flow in applicable tracks, and the distinctions between multi-mono and multi-channel formats. We’ll review basic methods for instantiating inserts, and throw in a few new tricks for simultaneously adding or deleting multiple inserts, as well as moving and copying them. We’ll look at several options for organizing plug-in menu listings, including basic preferences, custom plug-in favorites, and default EQ and compressor settings. We’ll identify the performance issues relevant to heavy use of plug-ins, and suggest appropriate settings for optimizing plug-in capabilities in mix sessions. We’ll revisit the concept of plug-in latency discussed earlier this week, and see how to mitigate the potential problems of phase cancellation. Finally, we’ll survey a variety of specific techniques that will be helpful when utilizing inserts. Complete the reading below, and then we’ll get started.

Inserts Versus Real-Time Plug-Ins

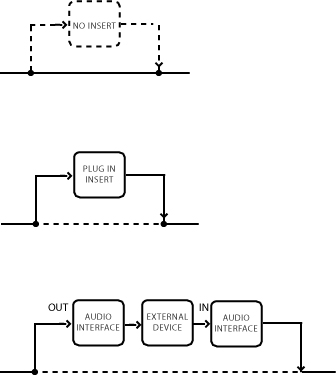

Inserts and real-time plug-ins are not equivalent. It’s easy to think of these as identical, since all real-time plug-ins are instantiated as channel inserts. However, hardware I/O channels can also be utilized for inserts, and this has nothing to do with internal signal processing. We’ll be dealing with plug-ins almost exclusively here and will use the terms somewhat interchangeably, but keep in mind that there is an alternative.

Scroll past the plug-in submenu when instantiating an insert to access another submenu with hardware I/O options.

If your audio interface only supports two inputs and outputs, it won’t be possible to use hardware inserts. (You’d need at least one unused input and output channel, and the main stereo monitor outputs would preempt any others.)

When a plug-in is inserted in a channel, it interrupts the normal signal flow and routes audio through the plug-in software. When an I/O channel is inserted in the signal flow, audio is routed to the designated audio interface output channel, through an external device, and back through the corresponding audio interface input channel.

Dealing with Latency

First, how can you tell if the processing on a channel is causing latency? Phase cancellation might not be apparent if the volume level is low, so it’s a good idea to check the channel status directly. To do this in Pro Tools 10, just Command-click (Mac OS) or Control-click (Windows) on the Audio Volume indicator below any fader in the Mix window to cycle through its three displays (fader level, peak track level, and total track latency). If using version 11 or later, the Audio Volume indicator is the left display below the fader, and you can toggle between fader level and latency.

Track latency can also be viewed when delay compensation (discussed below) is active by selecting the Delay Compensation option in the Mix Window View.

Total track latency displayed in Pro Tools 10.

Latency displayed in Pro Tools 12.

Latency is measured in samples, so in the example above the delay will be approximately 1.5 milliseconds assuming a sample rate of 44.1 kHz (64 ÷ 44,100). Depending upon the plug-ins being used, latency can be significant. In the next example, we’ll activate multiple inserts on a channel. Of the five inserts, all but the first introduce latency. Note how the total latency increases as we activate the plug-ins one-by-one.

Fortunately, this is readily mitigated. Although there are a few methods for dealing with latency, the easiest is to utilize Automatic Delay Compensation. ADC does all of the work for you, adjusting every track’s total delay as needed and updating these settings whenever plug-in instances are modified. It also compensates for the delays associated with busses and sends. It’s theoretically possible you’ll still need to use manual adjustments on occasion, since there’s a limit to the total delay compensation available. However, this will rarely—if ever—be the case, so delay compensation will usually be quick and easy. Here’s how it works:

If you want to use an old-school solution for latency, the following should be a workable solution:

-

Identify the channels that may need intervention, based on the scenarios we’ve discussed.

-

Identify the total latency on each channel, and note which channel has the highest latency.

-

Instantiate the TimeAdjuster plug-in on each affected channel other than the channel with the maximum latency. (Use the small, medium, or long depending upon the amount of correction needed.)

-

Set the TimeAdjuster delay on each channel so that the total latency matches the delay on the channel with the maximum latency.

-

Don’t forget to update the TimeAdjuster plug-in settings if you make a change in plug-in usage that alters the latency on the affected tracks.

This may sound like a hassle, and in fact it’s not the most enjoyable part of mixing. But you shouldn’t have too many instances that require intervention, so won’t need to spend a lot of time dealing with latency. Here’s the basic process in the same session:

Command-Option-click (Mac OS) or Control-Alt-click (Windows) on any level display to toggle to the delay time for all tracks. After we add the first adjustment, we can Option-click and drag (Mac; Alt using Windows) on the plug-in nameplate to duplicate it on another track.

Note that the above example was made using Pro Tools 10; the process should be equivalent in version 11, but the TimeAdjuster plug-in doesn’t seem to affect the latency indicator!

The foundation for Musicians and Songwriters is a 501(c)3 nonprofit dedicated to helping artist get their music to the world, helping all of humanity. Artist need our help to make it.

Leave a Reply